|

| (photo by K Walne) |

Edward first came to my attention in October 2019 with the publication of the hardback edition of his excellent Ghostland: In Search of a Haunted Country.

Ghostland tells of his "search of the ‘sequestered places’ of the British Isles, our lonely moors, our moss-covered cemeteries, our stark shores and our folkloric woodlands." and of the influence these places have exerted over some of the countries greatest writers of the uncanny such as Arthur Machen, William Hope Hodgson and M.R. James whose work he had returned to during turbulent times in his own life.

Alongside this the book also functions as both an autobiography and memoir of his relationships with the various members of his family and of the birdwatching hobby he shared with his brother in a moving meditation on love and loss and the power of stories, themes he also explored in his 2014 novel The Listeners (UK).

Ghostland is published in paperback on the 15th of October 2020 and you can buy it here - UK / US.

He can be found at - edwardparnell.com - and on Twitter.

We urge everyone with an interest in the writers we feature here on Wyrd Britain to check out Ghostland and we are immensely pleased to be able to present to you his selections.

..............................................................................................

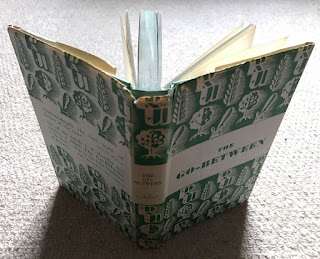

The Go-Between

L. P. Hartley

(Buy it here - UK / US)

Choosing just one book for this list is so difficult – I cycled through any number of contenders including: The Collected Ghost Stories of M. R. James, Alan Garner’s The Owl Service, The Usborne Guide to the Supernatural World, the stories of Algernon Blackwood, Arthur Machen or Walter de le Mare, or Janet and Colin Bord’s gazetteer of ancient sites, Mysterious Britain...

In the end though, I’ve settled on L. P. Hartley’s The Go-Between (1953). It’s a wonderful, haunting novel, about the naivety of youth, about class, about the mysteries of the English countryside (and its weather) – and about the complicatedness of human relationships. Along the way there are childish spells and curses, and significant encounters with a brooding deadly nightshade plant (“It looked the picture of evil and also the picture of health, it was so glossy and strong and juicy-looking”); Hartley himself also happened to be a very competent writer of supernatural short stories.

Above all though, The Go-Between is a novel dominated by an overwhelming sense of yearning for that which has been lost (whether that’s innocence, hope, or just time), and of the difficulties of trying to re-examine and make sense of our half-buried memories. It’s something that’s encapsulated in the book’s famous first line, a line which surely everyone is familiar with:

“The past is a foreign country: they do things differently there.”

At the novel’s heart is its young protagonist Leo Colston, whose aged older self begins his backwards-looking journey after discovering his childhood diary from 1900, hidden in the bottom of a cardboard box filled with various other forgotten reminders of that golden age: empty sea-urchins, two rusty magnets that have lost their magnetism, and “one or two ambiguous objects, pieces of things, of which the use was not at once apparent”.

Leslie Poles Hartley was born at the end of 1895 in the Fens at Whittlesey, not far from my own childhood home in south Lincolnshire. As fellow flatlanders, Hartley and I were bewitched by the otherness of the wooded Norfolk countryside after being raised among the empty expanse of all those breeze-stripped washes and ruler-straight Fenland droves. In the summer of 1909, Hartley was invited by a rather grander classmate, Moxey (his surname an approximation of The Go-Between’s Maudsley), to stay at West Bradenham Hall, a few miles from my own grandmother’s small west Norfolk cottage (Bradenham became Brandham in the novel). The hall – the ancestral home of Henry Rider Haggard – had been rented by the Moxeys, and it was at Bradenham where much of Hartley’s later inspiration for the novel originally stemmed. The novel’s setting in Norfolk is another aspect that draws me to it, given that I have now myself lived in the county for longer than I have anywhere else. (The excellent 1971 Joseph Losey film adaptation starring Julie Christie and Alan Bates was also filmed in my adopted county.)

The Go-Between, with its naïve narrator – the embodiment of ‘greenness’ in his newly gifted Lincoln Green suit – who is privy to an adult world beyond his comprehension, certainly fed into my novel The Listeners, a slice of WWII-set Eastern gothic, brooding nature, and family secrets set in a village based around the tiny hamlet in which my grandmother lived. And it also fed into my second book, the narrative non-fiction Ghostland, in which I attempt my own rather Leo-like examination of various haunted writers, artists and filmmakers, as well as my own haunted past…

Song

L. P. Hartley

(Buy it here - UK / US)

Choosing just one book for this list is so difficult – I cycled through any number of contenders including: The Collected Ghost Stories of M. R. James, Alan Garner’s The Owl Service, The Usborne Guide to the Supernatural World, the stories of Algernon Blackwood, Arthur Machen or Walter de le Mare, or Janet and Colin Bord’s gazetteer of ancient sites, Mysterious Britain...

In the end though, I’ve settled on L. P. Hartley’s The Go-Between (1953). It’s a wonderful, haunting novel, about the naivety of youth, about class, about the mysteries of the English countryside (and its weather) – and about the complicatedness of human relationships. Along the way there are childish spells and curses, and significant encounters with a brooding deadly nightshade plant (“It looked the picture of evil and also the picture of health, it was so glossy and strong and juicy-looking”); Hartley himself also happened to be a very competent writer of supernatural short stories.

Above all though, The Go-Between is a novel dominated by an overwhelming sense of yearning for that which has been lost (whether that’s innocence, hope, or just time), and of the difficulties of trying to re-examine and make sense of our half-buried memories. It’s something that’s encapsulated in the book’s famous first line, a line which surely everyone is familiar with:

“The past is a foreign country: they do things differently there.”

At the novel’s heart is its young protagonist Leo Colston, whose aged older self begins his backwards-looking journey after discovering his childhood diary from 1900, hidden in the bottom of a cardboard box filled with various other forgotten reminders of that golden age: empty sea-urchins, two rusty magnets that have lost their magnetism, and “one or two ambiguous objects, pieces of things, of which the use was not at once apparent”.

Leslie Poles Hartley was born at the end of 1895 in the Fens at Whittlesey, not far from my own childhood home in south Lincolnshire. As fellow flatlanders, Hartley and I were bewitched by the otherness of the wooded Norfolk countryside after being raised among the empty expanse of all those breeze-stripped washes and ruler-straight Fenland droves. In the summer of 1909, Hartley was invited by a rather grander classmate, Moxey (his surname an approximation of The Go-Between’s Maudsley), to stay at West Bradenham Hall, a few miles from my own grandmother’s small west Norfolk cottage (Bradenham became Brandham in the novel). The hall – the ancestral home of Henry Rider Haggard – had been rented by the Moxeys, and it was at Bradenham where much of Hartley’s later inspiration for the novel originally stemmed. The novel’s setting in Norfolk is another aspect that draws me to it, given that I have now myself lived in the county for longer than I have anywhere else. (The excellent 1971 Joseph Losey film adaptation starring Julie Christie and Alan Bates was also filmed in my adopted county.)

The Go-Between, with its naïve narrator – the embodiment of ‘greenness’ in his newly gifted Lincoln Green suit – who is privy to an adult world beyond his comprehension, certainly fed into my novel The Listeners, a slice of WWII-set Eastern gothic, brooding nature, and family secrets set in a village based around the tiny hamlet in which my grandmother lived. And it also fed into my second book, the narrative non-fiction Ghostland, in which I attempt my own rather Leo-like examination of various haunted writers, artists and filmmakers, as well as my own haunted past…

Song

Windy Old Weather

Bob Roberts (1960)

My musical tastes are rather eclectic, albeit also quite rooted in the past – ranging from ‘60s garage and Northern Soul, through to New Wave, ‘80s electronica, ‘70s-era Springsteen, and various whimsical soundtracks to the children’s TV series of my youth (like Bagpuss or The Moomins). I’m also partial to the odd spot of folk music and, with a strong love of the ocean, have become strangely attracted to old sea shanties. One such that really sticks with me is on an EP single I own dating from 1960 titled Windy Old Weather. It includes wonderful artwork and an extensively illustrated booklet, describing itself as a “record of sea shanties and saltwater ballads with skipper Bob Roberts”.

Alfred William “Bob” Roberts (1907–1982) was a sailor, folk singer and collector of traditional British maritime songs. He was also the author of a number of nautical books, and known for various appearances in the 1950s on BBC radio and television. As well as being a vocalist, he also played the melodeon, a “British chromatic button accordion”.

I enjoy all of the shanties on the record, but the one that really sticks out for me is the title track. Its back and forth rhythm mimics the North Sea’s swell, and it has me hooked with its opening line: “As we were a-fishing off Haisboro’ Light…” (Haisboro – spelled, in true Norfolk fashion as Happisburgh – is a village on the county’s north-east coast that’s gradually being washed away by the unrelenting sea.)

I enjoy all of the shanties on the record, but the one that really sticks out for me is the title track. Its back and forth rhythm mimics the North Sea’s swell, and it has me hooked with its opening line: “As we were a-fishing off Haisboro’ Light…” (Haisboro – spelled, in true Norfolk fashion as Happisburgh – is a village on the county’s north-east coast that’s gradually being washed away by the unrelenting sea.)

As the song progresses we’re introduced to various fishes, which in turn breach out of the water and seemingly speak to the crew of the boat – they half-taunt and tell the fishermen of the turning weather, warning them that they ought to head back towards land. It’s all rather magical and poetic (“Then up rears a conger as long as a mile / Winds comin’ easterly, he says with a smile”), certainly whimsical (I could picture it, for instance, as one of the stories told by the rag doll Madeleine in Bagpuss), but utterly compelling – and all delivered in Roberts’s endearing salty Dorset drawl.

It’s a song that makes me long to be at the coast, gazing down from those crumbling cliffs by Happisburgh Light into the grey-dark of the sea. It also makes me want to write about the ocean, a challenge that hopefully one day I’ll undertake.

Film

Bob Roberts (1960)

My musical tastes are rather eclectic, albeit also quite rooted in the past – ranging from ‘60s garage and Northern Soul, through to New Wave, ‘80s electronica, ‘70s-era Springsteen, and various whimsical soundtracks to the children’s TV series of my youth (like Bagpuss or The Moomins). I’m also partial to the odd spot of folk music and, with a strong love of the ocean, have become strangely attracted to old sea shanties. One such that really sticks with me is on an EP single I own dating from 1960 titled Windy Old Weather. It includes wonderful artwork and an extensively illustrated booklet, describing itself as a “record of sea shanties and saltwater ballads with skipper Bob Roberts”.

Alfred William “Bob” Roberts (1907–1982) was a sailor, folk singer and collector of traditional British maritime songs. He was also the author of a number of nautical books, and known for various appearances in the 1950s on BBC radio and television. As well as being a vocalist, he also played the melodeon, a “British chromatic button accordion”.

I enjoy all of the shanties on the record, but the one that really sticks out for me is the title track. Its back and forth rhythm mimics the North Sea’s swell, and it has me hooked with its opening line: “As we were a-fishing off Haisboro’ Light…” (Haisboro – spelled, in true Norfolk fashion as Happisburgh – is a village on the county’s north-east coast that’s gradually being washed away by the unrelenting sea.)

I enjoy all of the shanties on the record, but the one that really sticks out for me is the title track. Its back and forth rhythm mimics the North Sea’s swell, and it has me hooked with its opening line: “As we were a-fishing off Haisboro’ Light…” (Haisboro – spelled, in true Norfolk fashion as Happisburgh – is a village on the county’s north-east coast that’s gradually being washed away by the unrelenting sea.)As the song progresses we’re introduced to various fishes, which in turn breach out of the water and seemingly speak to the crew of the boat – they half-taunt and tell the fishermen of the turning weather, warning them that they ought to head back towards land. It’s all rather magical and poetic (“Then up rears a conger as long as a mile / Winds comin’ easterly, he says with a smile”), certainly whimsical (I could picture it, for instance, as one of the stories told by the rag doll Madeleine in Bagpuss), but utterly compelling – and all delivered in Roberts’s endearing salty Dorset drawl.

It’s a song that makes me long to be at the coast, gazing down from those crumbling cliffs by Happisburgh Light into the grey-dark of the sea. It also makes me want to write about the ocean, a challenge that hopefully one day I’ll undertake.

Film

Dead of Night

(Ealing Studios, 1945)

(Buy it here - UK / US)

Warning – this contains spoilers

“If only I’d left here when I wanted to, when I still had a will of my own. You tried to stop me. You wouldn’t have done if you’d have known,” says Mervyn Johns’s troubled protagonist Walter Craig to Frederick Valk’s Freud-like psychiatrist Dr Van Straaten, prior to the inevitable, nightmarish end sequence of the classic 1945 Ealing Studios portmanteau horror film Dead of Night. Inevitable, because Craig is a man who wakes each morning from the same unconscious, barely recalled terror – and because he has already informed us how events are set to play out.

At the start of the film, Craig arrives in a reverie of déjà vu at a Kentish farmhouse he’s never previously visited, summoned there by a man he’s unacquainted with to look into redesigning the place. The architect has the dawning realisation that the house forms the backdrop to his nightly recurring dream, and that his fellow guests, all uncannily familiar to him despite their having never met, might be mere phantoms in his head.

Dead of Night contains five embedded narratives recalled by the occupants of the farmhouse. The first concerns a premonition of an avoided future – its most memorable moment is the fateful line uttered by Miles Malleson’s bus conductor/hearse driver: “Just room for one inside, sir.” (The segment is loosely based upon a short story by E. F. Benson.)

The next, a gothic children’s Christmas party that’s haunted by the ghost of a murdered small boy (and inspired by the murder at the heart of Kate Summercale’s true-crime book The Suspicions of Mr Whicher), is much more atmospheric, as is the third tale, that of an antique mirror that possesses its owner. Some questionable light relief is provided by Basil Radford and Naunton Wayne’s comedic, ghostly golf shenanigans (a reprise of their sport-obsessed cameo in Hitchcock’s 1938 The Lady Vanishes), before we come to the last and most celebrated of the stories, in which Michael Redgrave’s unhinged ventriloquist Maxwell Frere is driven insane by his papier mâché companion.

However, it’s the film’s masterful, playful framing device (directed by Basil Dearden) that sets Dead of Night apart, providing both its end and its beginning. Because, at its climax we witness, once more, Craig’s identical arrival along a tree-lined country lane that followed on from the opening credits. First, though, we must spin back four minutes, to the moment Mervyn Johns’s character rises from his chair in the flickering, fire-lit lounge.

Craig saunters towards the camera and the seated Dr Van Straaten, blankly demanding why he had to set into motion what’s about to come: “Oh Doctor, why did you have to break your glasses?” Craig towers behind the psychiatrist, removing his tie and strangling the larger man with a casual ease. A voice in his head urges Craig to hide and suddenly he finds himself in the familiar surroundings of the Christmas masquerade of the film’s second section.

The teenage Sally Ann Howes and a massed rank of costumed children urge the murderer to join in their game of hide and seek. Craig flees up the same shadowed staircase Howes herself had previously traversed en route to offering comfort to the ghostly young Victorian victim, only this time the scene is skewed at an angle that recalls another film with a similarly mind-blowing ending: Robert Wiene’s masterpiece of German expressionism The Cabinet of Dr Caligari (1919). Craig pauses in front of the haunted mirror of director Robert Hamer’s third segment, which shimmers in a psychedelic haze, prior to accosting Hayes and dragging her to the attic. There, he strikes the blow to her face he earlier predicted he’d be powerless to prevent.

Without warning, Craig is seated alongside the malevolent, foul-mouthed puppet from the final story (stylishly directed by Alberto Cavalcanti, as was the Christmas party). Hugo urges Craig to “take a seat, sucker”, as the camera pans around the gathered cabaret faces that leer down at the guilty man – and the audience. The strangler is carried aloft to a prison cell manned by Miles Malleson from the first tale: “Just room for one inside, sir,” he once more intones, this time with added relish. On the opposite side of the cell from where Craig cowers, sits Hugo, who, in the most menacing scene of the film, takes to his feet and begins to walk. The crowd of onlookers grin like hungry wraiths through the bars of the door as an undersized actor in dummy make-up strides towards Johns and places his hands on the architect’s throat, before the shot pulls rapidly back to reveal the silhouetted darkness. Now Craig is lying in the bland, comforting surroundings of his own house, awakened by the sound of the phone beside his marital bed that’s ringing to summon him, once more, to that all-too-familiar cottage.

It’s a future of purgatorial dread and guilt that must hardly have been the uplifting tonic conflict-weary audiences were expecting when the film opened in London just one week after the second world war had finally reached its own grim conclusion.

It’s also a film that I can endlessly rewatch, marvelling at the way its storylines entwine and at how masterfully its ending – the most difficult of things to pull off – is handled.

Watch it here - http://www.veoh.com/watch/v87902984jRrcN5AB

..........................................................................................

If you enjoy what we do here on Wyrd Britain and would like to help us continue then we would very much welcome a donation towards keeping the blog going - paypal.me/wyrdbritain

(Ealing Studios, 1945)

(Buy it here - UK / US)

Warning – this contains spoilers

“If only I’d left here when I wanted to, when I still had a will of my own. You tried to stop me. You wouldn’t have done if you’d have known,” says Mervyn Johns’s troubled protagonist Walter Craig to Frederick Valk’s Freud-like psychiatrist Dr Van Straaten, prior to the inevitable, nightmarish end sequence of the classic 1945 Ealing Studios portmanteau horror film Dead of Night. Inevitable, because Craig is a man who wakes each morning from the same unconscious, barely recalled terror – and because he has already informed us how events are set to play out.

At the start of the film, Craig arrives in a reverie of déjà vu at a Kentish farmhouse he’s never previously visited, summoned there by a man he’s unacquainted with to look into redesigning the place. The architect has the dawning realisation that the house forms the backdrop to his nightly recurring dream, and that his fellow guests, all uncannily familiar to him despite their having never met, might be mere phantoms in his head.

Dead of Night contains five embedded narratives recalled by the occupants of the farmhouse. The first concerns a premonition of an avoided future – its most memorable moment is the fateful line uttered by Miles Malleson’s bus conductor/hearse driver: “Just room for one inside, sir.” (The segment is loosely based upon a short story by E. F. Benson.)

The next, a gothic children’s Christmas party that’s haunted by the ghost of a murdered small boy (and inspired by the murder at the heart of Kate Summercale’s true-crime book The Suspicions of Mr Whicher), is much more atmospheric, as is the third tale, that of an antique mirror that possesses its owner. Some questionable light relief is provided by Basil Radford and Naunton Wayne’s comedic, ghostly golf shenanigans (a reprise of their sport-obsessed cameo in Hitchcock’s 1938 The Lady Vanishes), before we come to the last and most celebrated of the stories, in which Michael Redgrave’s unhinged ventriloquist Maxwell Frere is driven insane by his papier mâché companion.

However, it’s the film’s masterful, playful framing device (directed by Basil Dearden) that sets Dead of Night apart, providing both its end and its beginning. Because, at its climax we witness, once more, Craig’s identical arrival along a tree-lined country lane that followed on from the opening credits. First, though, we must spin back four minutes, to the moment Mervyn Johns’s character rises from his chair in the flickering, fire-lit lounge.

Craig saunters towards the camera and the seated Dr Van Straaten, blankly demanding why he had to set into motion what’s about to come: “Oh Doctor, why did you have to break your glasses?” Craig towers behind the psychiatrist, removing his tie and strangling the larger man with a casual ease. A voice in his head urges Craig to hide and suddenly he finds himself in the familiar surroundings of the Christmas masquerade of the film’s second section.

The teenage Sally Ann Howes and a massed rank of costumed children urge the murderer to join in their game of hide and seek. Craig flees up the same shadowed staircase Howes herself had previously traversed en route to offering comfort to the ghostly young Victorian victim, only this time the scene is skewed at an angle that recalls another film with a similarly mind-blowing ending: Robert Wiene’s masterpiece of German expressionism The Cabinet of Dr Caligari (1919). Craig pauses in front of the haunted mirror of director Robert Hamer’s third segment, which shimmers in a psychedelic haze, prior to accosting Hayes and dragging her to the attic. There, he strikes the blow to her face he earlier predicted he’d be powerless to prevent.

Without warning, Craig is seated alongside the malevolent, foul-mouthed puppet from the final story (stylishly directed by Alberto Cavalcanti, as was the Christmas party). Hugo urges Craig to “take a seat, sucker”, as the camera pans around the gathered cabaret faces that leer down at the guilty man – and the audience. The strangler is carried aloft to a prison cell manned by Miles Malleson from the first tale: “Just room for one inside, sir,” he once more intones, this time with added relish. On the opposite side of the cell from where Craig cowers, sits Hugo, who, in the most menacing scene of the film, takes to his feet and begins to walk. The crowd of onlookers grin like hungry wraiths through the bars of the door as an undersized actor in dummy make-up strides towards Johns and places his hands on the architect’s throat, before the shot pulls rapidly back to reveal the silhouetted darkness. Now Craig is lying in the bland, comforting surroundings of his own house, awakened by the sound of the phone beside his marital bed that’s ringing to summon him, once more, to that all-too-familiar cottage.

It’s a future of purgatorial dread and guilt that must hardly have been the uplifting tonic conflict-weary audiences were expecting when the film opened in London just one week after the second world war had finally reached its own grim conclusion.

It’s also a film that I can endlessly rewatch, marvelling at the way its storylines entwine and at how masterfully its ending – the most difficult of things to pull off – is handled.

Watch it here - http://www.veoh.com/watch/v87902984jRrcN5AB

..........................................................................................

If you enjoy what we do here on Wyrd Britain and would like to help us continue then we would very much welcome a donation towards keeping the blog going - paypal.me/wyrdbritain

Affiliate links are provided for your convenience and to help mitigate running costs.

No comments:

Post a Comment