This month: J.M. Walsh

Jamie Walsh is the owner / publisher of Broodcomb Press and under various guises the writer of books published under that banner. His works touch on many of the touchstones that we hold so dear here at Wyrd Britain such as Arthur Machen, Sylvia Townsend Warner and Algernon Blackwood exploring fictions hinterlands with an emphasis on the strange and the uncanny.

If you haven't already then we at Wyrd Britain heartily recommend that you dig into the dark delights of Broodcomb's catalogue at...

www.broodcomb.co.uk

..................................................................

Book/Author

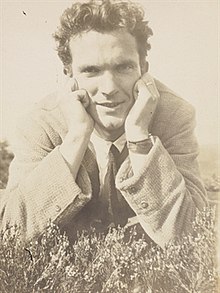

Neil M. Gunn

Neil Miller Gunn wrote numerous novels, and the best of them are astonishingly immersive experiences of worlds that – even when recognisable – remain elusive and undefined.

Part of this is a curious reticence in his writing to naming the numinous, which lends his narratives a consuming hesitance towards the exploration of wonder. I intuit a little embarrassment in the books as speaking aloud would run counter to the grain of his Highland gruffness, yet also a defiance because, for Gunn, aspects of being human that reach out of the ordinary are the chief part of life.

For all its relative opaqueness, his writing is remarkable because the effect is of a ‘pointing towards’ that which in nature and human experience is (in a non-religious sense) sacred or divine, without ever coming out and naming it (if that is ever possible). Reading his books over the years, I became convinced he was a figure of Highland Zen only to find in his autobiography, ‘The Atom of Delight’, that he actually was deeply taken with Eugen Herrigel’s ‘Zen in the Art of Archery’, finding much in it that resonated with his world view.

The numinous is found in most of his novels, particularly ‘The Well at the World’s End’ and ‘The Other Landscape’, yet an early loose trilogy of novels creates worlds of the human sacred that are among the most engrossing I’ve ever read. ‘Sun Circle’ puts the reader in Dark Ages tribal Scotland, Christianity newly arrived but in great tension with the old religion, at the time of Viking raids. It recalls William Golding’s ‘The Inheritors’ and, in a more oblique way, Sylvia Townsend Warner’s ‘The Corner That Held Them’, in the ability to see the world as the characters would have seen it. One character’s dawning realisation of what happens at the stones lives with me to this day as a moment of unfolding terror.

It is the second of the loose trilogy, ‘Butcher’s Broom’, that I return to. The novel is set in the Highland Clearances, but the heart of the book is less the historic and economic drivers than the effects on one community, which Gunn draws so carefully that the strangeness of how such communities worked becomes seductive, and the descriptions of the combined waulking and ceilidh feel familiar and deeply, deeply other at the same time – a human existence that is both within reach and lost forever.

It is the second of the loose trilogy, ‘Butcher’s Broom’, that I return to. The novel is set in the Highland Clearances, but the heart of the book is less the historic and economic drivers than the effects on one community, which Gunn draws so carefully that the strangeness of how such communities worked becomes seductive, and the descriptions of the combined waulking and ceilidh feel familiar and deeply, deeply other at the same time – a human existence that is both within reach and lost forever.

Even the novels that are resolutely of this world retain this sense of disquiet, as if the locations and events exist at least partly in myth. Plotwise, ‘The Lost Chart’ is a standard-for-its-time spy narrative… and yet the characters move in a twilight world that seems unconnected to our own. ‘The Drinking Well’ is about disgrace and change and the lure of politics and the modern… and yet the book begins and ends at a mythic source that makes all human concerns so much fluff. The scene where young Iain Cattanach is driving the sheep when the blizzard beds in is more dread-inspiring and consuming than any thriller.

It’s doubtless overstating things, but Neil M. Gunn is a lost Nobel Laureate.

Film

Ratcatcher

I bought this for next to nothing, and you can still pick up copies for a couple of pounds, which seems remarkable. If ever there was a film deserving of the full pomp of a Eureka Masters of Cinema release, it’s Lynne Ramsay’s ‘Ratcatcher’.

What’s most remarkable is that I’ve seen this film a number of times, and even now the details of it swim about in my memory as if I’m viewing it underwater. Whenever I think about the film, what comes to mind are not films that feel thematically similar but Tarkovsky films: ‘Stalker’ and ‘Mirror’. If pinned down to explain why, I don’t think I could give a coherent answer.

Part of it is the sense I have that – for all ‘Ratcatcher’s anchorage to a particular time and place (and politics) – the film becomes archetypal. Set in Glasgow in 1973 at a time of strikes, redevelopment and relocation, I’ve the feeling I’m watching a film that has deep bones that reach far into human experience. Made in 1999, the film looks back a quarter of a century but equally could be a document of a centuries-old way of life.

There are two scenes in particular that stand out as moments that are both resonant and weird. I won’t describe them in detail. The first concerns one of the adult characters, seen after an act of violence (and I suspect retributive violence) that points to a world the young protagonist will doubtless inherit. It is a moment of glimpsed dread that worked its way into my dreams when I first saw the film.

The second concerns the fate of Kenny, a mouse, who goes on a journey, footage of which (strangely and impossibly) exists—

Music

Spoonfed Hybrid

I bought this on vinyl when it came out, and although the vinyl was lost the album has remained one I never tire of listening to, and still sounds inventive and new. The wealth of ideas in Spoonfed Hybrid is remarkable considering they were a duo; the album sounds as though Pale Saints, a string quartet, a coldwave outfit and Jan Švankmajer were in the same accident and they all walked away essentially unharmed—

I’ve never got to the bottom of the lyrics, and even today details are new. (In writing this, it’s only now (28 years later) that I’ve realised ‘Boys in Zinc’ must be a reference to the extraordinary book by Svetlana Alexievich about the experiences of Russian boys and men in Afghanistan.) The songs surprise me every time I listen to them: I’ve heard them so many times yet they always feel subtly different, new. I understand intellectually they haven’t changed in the meantime, but emotionally I’m not quite so certain—

‘A Pocketful of Dust’ is a case in point. I’ve no idea what it’s about, yet the tale the song tells is one I know at the level of my own lived experience. It’s a torch song, weird and committed, yet also a dark folk tale. ‘Boys in Zinc’ is beautiful, and the closing seconds spiral upwards. ‘Messrs. Hyde’ – only on the accompanying 7” – is (ironically considering the album was not released on 4AD) two minutes of disquieting piano-led anxiety that contains elements of ‘The Serpent’s Egg’-era Dead Can Dance, This Mortal Coil and Bauhaus. And I’m reasonably certain other admirers of the album would reject those entirely in favour of another three, perfectly-valid comparisons.

Strangely, the album did well in France, and I hear elements even today in bands like Audiac. If the record is referenced at all, however, it’s smoothed into ‘shoegazing’ or dismissed as ‘dreampop’. Spoonfed Hybrid is neither; it’s a beautiful and unsettlingly strange album that was never repeated.

........................................................................

If you enjoy what we do here on Wyrd Britain and would like to help us continue then we would very much welcome a donation towards keeping the blog going - paypal.me/wyrdbritain

Film

Ratcatcher

I bought this for next to nothing, and you can still pick up copies for a couple of pounds, which seems remarkable. If ever there was a film deserving of the full pomp of a Eureka Masters of Cinema release, it’s Lynne Ramsay’s ‘Ratcatcher’.

What’s most remarkable is that I’ve seen this film a number of times, and even now the details of it swim about in my memory as if I’m viewing it underwater. Whenever I think about the film, what comes to mind are not films that feel thematically similar but Tarkovsky films: ‘Stalker’ and ‘Mirror’. If pinned down to explain why, I don’t think I could give a coherent answer.

Part of it is the sense I have that – for all ‘Ratcatcher’s anchorage to a particular time and place (and politics) – the film becomes archetypal. Set in Glasgow in 1973 at a time of strikes, redevelopment and relocation, I’ve the feeling I’m watching a film that has deep bones that reach far into human experience. Made in 1999, the film looks back a quarter of a century but equally could be a document of a centuries-old way of life.

There are two scenes in particular that stand out as moments that are both resonant and weird. I won’t describe them in detail. The first concerns one of the adult characters, seen after an act of violence (and I suspect retributive violence) that points to a world the young protagonist will doubtless inherit. It is a moment of glimpsed dread that worked its way into my dreams when I first saw the film.

The second concerns the fate of Kenny, a mouse, who goes on a journey, footage of which (strangely and impossibly) exists—

Music

Spoonfed Hybrid

I bought this on vinyl when it came out, and although the vinyl was lost the album has remained one I never tire of listening to, and still sounds inventive and new. The wealth of ideas in Spoonfed Hybrid is remarkable considering they were a duo; the album sounds as though Pale Saints, a string quartet, a coldwave outfit and Jan Švankmajer were in the same accident and they all walked away essentially unharmed—

I’ve never got to the bottom of the lyrics, and even today details are new. (In writing this, it’s only now (28 years later) that I’ve realised ‘Boys in Zinc’ must be a reference to the extraordinary book by Svetlana Alexievich about the experiences of Russian boys and men in Afghanistan.) The songs surprise me every time I listen to them: I’ve heard them so many times yet they always feel subtly different, new. I understand intellectually they haven’t changed in the meantime, but emotionally I’m not quite so certain—

‘A Pocketful of Dust’ is a case in point. I’ve no idea what it’s about, yet the tale the song tells is one I know at the level of my own lived experience. It’s a torch song, weird and committed, yet also a dark folk tale. ‘Boys in Zinc’ is beautiful, and the closing seconds spiral upwards. ‘Messrs. Hyde’ – only on the accompanying 7” – is (ironically considering the album was not released on 4AD) two minutes of disquieting piano-led anxiety that contains elements of ‘The Serpent’s Egg’-era Dead Can Dance, This Mortal Coil and Bauhaus. And I’m reasonably certain other admirers of the album would reject those entirely in favour of another three, perfectly-valid comparisons.

Strangely, the album did well in France, and I hear elements even today in bands like Audiac. If the record is referenced at all, however, it’s smoothed into ‘shoegazing’ or dismissed as ‘dreampop’. Spoonfed Hybrid is neither; it’s a beautiful and unsettlingly strange album that was never repeated.

........................................................................

If you enjoy what we do here on Wyrd Britain and would like to help us continue then we would very much welcome a donation towards keeping the blog going - paypal.me/wyrdbritain

Affiliate links are provided for your convenience and to help mitigate running costs.

No comments:

Post a Comment