This month, John Howard

John is an author and essayist working in the fields of the uncanny and the fantastical. His writing first came to my attention through his collaborations with Mark Valentine on their sublime 'The Collected Conoisseur' and since then I've been fortunate to encounter a number of his pieces in various anthologies and journals.

His books include 'The Defeat of Grief', 'The Lustre of Time', 'The Silver Voices', 'Written by Daylight', 'Buried Shadows', 'Secret Europe' and 'Inner Europe' (both with Mark Valentine) and the upcoming 'The Voice of Air'. His work has been published by some of the finest small press publishers for fantastical fiction around including Tartarus Press, Ex Occidente Press, Swan River Press and Egaeus Press amongst others, He currently also writes the 'Camera Obscura' review column for Wormwood, a journal concerned with the fantastic, supernatural and decadent in literature.

We are delighted to have John sharing his choices here on Wyrd Britain.

...................................................................................

Book

The Novel of the White Powder and Other Stories

Arthur Machen

By the time I had discovered Arthur Machen in the late 1970s, nothing by him was in print. Although a hardcover edition of Tales of the Horror and the Supernatural was supposedly available, being listed in the reference volume the size of a lectern bible that the friendly man in my town’s only bookshop had consulted, this turned out to be illusory, and I had to make do with scanning the shelves of second-hand bookshops for paperback editions of Machen’s stories.

One of the gaudiest – the cover is a delicious masterpiece evoking Victorian Gothic horror and the corrupting consequences of trespassing over the boundaries – was a compilation called The Novel of the White Powder and Other Stories, which Corgi Books had published in 1965. Two of its three stories I already had in other paperbacks and had read over and over again, but the other was “A Fragment of Life”: a long story, some 80 pages according to the table of contents, and one I had never heard of before. In any case, I would’ve bought the book simply for its cover, but with the prospect of a Machen tale new to me… I have the book in front of me now, and see that the price of 35p is still scrawled inside. I doubt that I ever spent 35p to such advantage.

“A Fragment of Life” is Machen at his most – well – Machenesque. We begin in the bedroom of Mr and Mrs Darnell, in London – but in the dream that Mr Darnell is awakening from, he has been elsewhere else entirely. Then we seem to be in a sort of suburban social comedy, not unlike The Diary of a Nobody (which surely Machen would have known and relished for its inside-job, deliberate, hilarious, utterly deadpan dismantling of middle-class pretensions). Mr Darnell is no Mr Pooter, but Darnell’s friend Wilson, for all his apparent nous, is such an obtuse fool that Mrs Pooter would have found a way of keeping her husband clear of his company. Machen is using his boxing gloves, and we are expected to realise it. But some time before, he had sharpened his best set of kitchen knives, but to a completely different end.

|

| Arthur Machen |

If this story is about one man it can be about me as well. Machen shows how a different, deeper, truly fulfilling world can slowly resolve itself up through the apparently ‘real’ one. The bright but thin new paint is wearing off, and the solid work beneath is revealed at last.

We have been allowed to read an account of a transformation: and yet I for one can never quite see how it is done. Machen’s narrative is deceptively simple; yet he plays with time, shuffling memories and recollections like playing cards. And although an end is achieved, satisfactory and fulfilling and right, Machen himself had to intervene decisively in order to release us. The story is potentially of infinite length, but we have to be free to discover it and enter it for ourselves.

I must stop too.

Film

Penda’s Fen

Buy it here

No doubt I was a strange teenager. For example, I always knew when the equinoxes and solstices were, and tried to observe them, to note another stage in the recurring passage of the years. It was easier for sunsets than sunrises, so I’d walk to some place where there was a clear horizon – and watch. I confirmed that the sun would set behind a certain tree on 21 June – and presumably on every 21 June for as long as the tree stood. Then I’d go back home again, my head full of compass-points and the sense of one more season gone and another beginning.

I’m sure this is very much what I would have done on 21 March 1974. I now also know for certain something else that I did do, later that evening. I was usually allowed to stay up to watch Play for Today, and so I saw that week’s offering, Penda’s Fen. I was allowed to witness a vision.

I did not remember the name of this English legend – legend in many senses – that I was lucky enough to have experienced. But when I saw it again recently I knew. Over the years I had never forgotten some of its images. Only a few, but those clearly had staying-power and had sunk deep, becoming part of the private stock of interior pictures to be summoned and run and re-run, whether by conscious invitation – or not.

There was the main character, Stephen: not yet a man, but much closer to it than I was – wandering the summer landscape, encountering gods and demons and Jesus. The familiar being invaded by something else entirely and leaving its mark. Or was it all in his mind? Adolescence is difficult. There’s a churning sea of beliefs, desires, challenges. Also the challenging of what and who we are and thought we knew. The film jumped into all this and mixed the ancient with the contemporary, all against a setting of fields and hills that has survived well the nearly fifty years that have passed.

There was the main character, Stephen: not yet a man, but much closer to it than I was – wandering the summer landscape, encountering gods and demons and Jesus. The familiar being invaded by something else entirely and leaving its mark. Or was it all in his mind? Adolescence is difficult. There’s a churning sea of beliefs, desires, challenges. Also the challenging of what and who we are and thought we knew. The film jumped into all this and mixed the ancient with the contemporary, all against a setting of fields and hills that has survived well the nearly fifty years that have passed.‘Is it strikers who pillage our earth, ransack it, drain it dry for quick gain, to hand on nothing but dust to the children of tomorrow?’ asks Arne, the village radical, a television playwright who grows his own vegetables. I remember feeling the uncertainties of the years around 1974: strikes, power-cuts, three-day week, the oil crisis, inflation, the possibility of nuclear war – and so on.

Arne’s words would have been as disturbing to me as they were to Stephen. I used to read the Daily Mail that appeared on the doormat on weekday mornings before breakfast. Arne goes on to connect the events of the day with the surrounding countryside: ‘Poets have hymned the spirit of this landscape… Farmland and pasture now, an ancient fen. The earth beneath your feet feels solid there. It is not.’ He doesn’t mean to talk about anything supernatural, but that makes no difference. For Stephen nothing is solid any more, and Penda’s Fen chronicles his slow realisation of who he really is, of his potential. His parents had remarked on his lack of self-awareness – but Stephen is going to be made aware, whether he likes it or not, of things that will transform him. As he must, the sunlit Elgarian landscape, with all its sunshine, wheat, cottages, hidden violence and centuries of blood, has to come of age too.

I’m sure I didn’t ever seriously imagine that I would see that tomorrow as Arne described – ransacked. But now I’m there I know that there is always more to learn about myself, and people and things to gain better awareness of. And I know that I want to embrace the final words of the film, spoken by (an imagined?) King Penda: ‘Stephen be secret, child be strange: dark, true, impure and dissonant. Cherish our flame. Our dawn shall come.’

Album

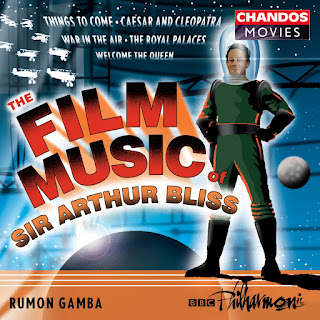

Things to Come: Concert Music from the Film (from The Film Music of Sir Arthur Bliss)

Buy it here

The film Things to Come (1936) was the innovative and flawed masterpiece by Alexander Korda and H.G. Wells loosely based on Wells’ novel The Shape of Things to Come (1933). From the beginning Wells had wished Arthur Bliss’ music to be ‘a part of the constructive scheme of the film’ and not ‘tacked on’. Inevitably it was not possible to achieve this well-intentioned outcome. Bliss went ahead and wrote his music, some of which was then in effect tacked on to the scenes as they finally emerged on film.

However, Bliss had also prepared an arrangement of the music as an orchestral suite in its own right, and this was first performed before the film was released. Over the decades there have been several attempts to reconstruct a ‘complete’ suite of Bliss’ music, seeking out and including work that had never made it into the film or previous orchestral versions.

This version from 2001 is considered definitive. As much as I like to watch the film, with its tremendous sets and dramatic set-pieces, letting the music complement the often clunky and preachy dialogue, now that it is available I also enjoy listening to this version of the music and imagining aspects of the film unwinding with it – both film and integral music as Wells and Bliss first envisaged.

I close my eyes… I react to four of the eleven sections in particular: “Prologue” (1) and the linked “Excavation”, “The Building of the New World”, and “Machines” (7-9). The Prologue sets the scene (in the film a much shorter version was used for the opening credits). The music is solemn and full of foreboding: war threatens. In the film, the citizens of Everytown (clearly intended to echo London, the Imperial Capital, with a great domed building dominating the skyline) are preparing to celebrate Christmas. Housewives buy turkeys, children gawp at toys in the brightly-lit shop windows, and carol-singers are out – snatches of tunes and singing are intercut – all as the headlines on newspaper vendors’ placards get worse. Then war does break out. Everytown is bombed; gas is used. The ‘Blitz’ scenes are highly effective and were prescient. London’s people and buildings are pulverised. Its soil is torn up. “And so we end an age”: these words spoken towards the end of the film are also appropriate at this point.

War drags on. Decades later it becomes possible to begin reconstruction of the ravaged world. Bliss’ music is clanging and colourful, with pulsing beats and hammering percussion. Hope is returning. In the film this is a medley of industrial scenes, of mining and construction, with the human participants usually dwarfed by colossal machinery and gigantic caverns and structures. Otherwise they are the anonymous engineers, production workers, and labourers taken up by the benign and reasonable scientific rulers in order to shape a sane and efficient new world. I wonder if Wells was remembering this when he published his penultimate book, The Happy Turning, in 1945: ‘In these dreams I apprehend gigantic facades, vast stretches of magnificently schemed landscape, moving roads that will take you wherever you want to go instead of your taking them. “All this and more also,” I rejoice. And though endless lovely new things are achieved, nothing a human heart has loved will ever be lost.’

Unfashionable though it is, I confess that I always find Things to Come – film and music – a stirring and moving vision, and never more so in an era when wars are still threatened, dictators and populists posture and pronounce with no thought for the consequences, and humanity seems to be in love with its own suicide.

Music has its way: this can be dangerous, but not here. The end result is that the soil of Everytown has given-up its riches and resources, and has itself been sacrificed, for the new city is underground, properly ventilated and illuminated. The surface is once more a green and pleasant land. Is that our greatest illusion – or best hope?

..........................................................................................

If you enjoy what we do here on Wyrd Britain and would like to help us continue then we would very much appreciate a donation towards keeping the blog going - paypal.me/wyrdbritain

No comments:

Post a Comment